Abstract

Despite vast improvements in chemo-therapeutic interventions extensively extending the life span of patients with chronic and terminal diseases, there also is the unhappy extension of side- effects and adverse events. Thus, Health-Related Quality of Life (HR-QoL) becomes equally as important as length of life. Accurately, reliably, validly, and representatively measuring the on-going pulse beat of HR-QoL means ensuring optimal responses and response rates, which in turn means fostering and maximizing Survey Participants’ continued rapport, enlistment, engagement, and participation regarding HR-QoL research survey studies. This is generally true regarding all human subjects’ research. HR-QoL survey work at a nationally renowned Cancer Center recently identified an example of Potlatch or gift-giving (i.e., gifting), and its surrounding nuances, that were calculated and appear to evoke enhanced reciprocal engagement in a HR-QoL survey.

This work involves continuous, iterative marketing study. The intent of this field note is to describe the methodological phenomenon that may have epistemological and theoretical relevance for ubiquitously advancing the interest of health survey research. Specifically, the contention will be that considered, and tactically deployed Potlatch can serve as a mechanism for facilitating and enhancing health survey research as well as enhancing stronger social engagement in research and treatment for patients undergoing medical care for long-term, chronic illness. First, it can rejuvenate and refocus Survey Participants’ involvement. Second, it can serve as an entrée and springboard to further forge a social connection in the interest of research. Lessons Learned and implications are reported.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2022 Ralph J Johnson, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

“Potlatch” is an anthropological term coined for the practice of ritualistic gift giving (i.e., gifting) used by the indigenous North American tribes that focuses on the reaffirmation of social connections.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Marcel Mauss 2 used the term to refer to general exchange practices in societies of “total prestations” with comprehensive social implications, especially evoking social norms of reciprocity. The phenomenon in question first revealed itself fully during a face-to-face encounter that was part of an approved periodic, routine encounter for a Health Related-Quality of Life (HR-QoL)7 survey for refractory hematologic cancer patients conducted in a large nationally renowned Cancer Center located in Houston, TX—namely, UT-MD Anderson. The survey is a brief (approx. 5-10 minute) face-to-face pen-and-paper administered HR- QoL and included some minor paperwork to document the survey’s administration.

The hospital clinics where the survey takes place readily provide supplies of disposable standard inexpensive plastic pens or graphite pencils in publicly accessible bins that are sufficient to complete routine clinic or lab paperwork. Such pens are prone to be inefficient, unreliable, and the writing quality can be “sketchy.” Nevertheless, should patients inadvertently carry off the pens or pencils the cost is absorbable.

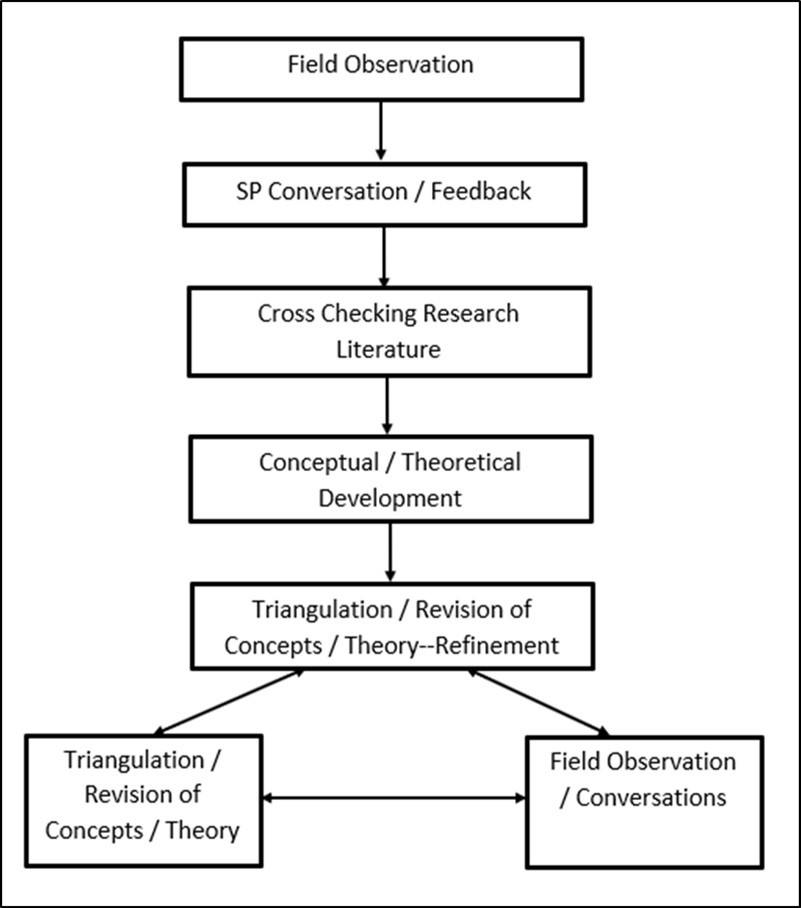

It is noteworthy, Denzin and Lincoln8 in their seminal work on the qualitative Case Study method assert that ‘the reporting is as important as empirical material collection and interpretation.’ Per their medical sociological approach, emphasis of this report is a “story-like” writing, which is crucial to case study reporting and the case study method. Nevertheless, a brief research design and case study analysis progression is provided in the form of an illustration see (Figure 1). 9

Case Study

One afternoon the Author approached a patient Survey Participant enrolled in the cancer registry, in the hospital’s laboratory services public lobby waiting area. The goal was to solicit his continued quarterly participation in the study’s HR-QoL Survey. The gentleman stood off to the side at a desk designated for completing lab paperwork. He was attempting to fill out a required paper label and a form to accompany his lab samples. He was using a disposable standard capped small pink ball-point pen he had retrieved from a nearby public bin. He was extremely frustrated and visibly irritated because he was having difficulty completing the paperwork due to the pen continually malfunctioning. The ink was too light, requiring constant re-writing. This was slowing him down and his lab appointment awaited. The pressure of the Author’s presence and the additional looming HR- QoL survey to complete did not help matters. He was already annoyed and quickly losing interest in the prospect of doing the survey as well.

This Author has learned of a way to engender and enhance cooperation and engagement in terms of completing the HR- QoL survey under such circumstances: to deftly offer a brand-new, more efficient, dependable (and pricey) handsome black gel .7 ink pen. This offering is not just ham-handing. Rather, the Author retrieves from the waist pocket of a lab coat a set of four such pens that are attached to the inside of the empty pen box from which 12 of the pens were originally sold. The pens are attached outside the box by their clips; so, the pens themselves are sheathed by the pen box. With outstretched hand, the Author says, “Here, they’re brand new. Take one, but do not touch the others. The pens have been disinfected. This is your pen to keep. It is a gift for your participation in this survey.” See (Photograph 1): Pen Gift Box Delivery System) The presentation is both aesthetically appealing and slightly dramatic.

Photograph 1.Pen Gift Box Delivery System

Thus, the presentation is like someone offering a cigarette from a pack to a smoker or a wrapped stick of chewing gum from a gum package. Noting the fact that the pens have been disinfected is important considering COVID and reinforces the hospital’s microbial consciousness and scrupulousness regarding infectious disease transmission prevention among immunocompromised patients. The gesture takes only a few seconds but makes the encounter feel special—as well as patients’ participation in the survey.

The Survey Participant in this case reached-out and slid a pen gently out from the carton without touching the other pens. He thanked the Author but said he would rather continue to use the pink pen he already had to complete the lab paperwork as this was the writing utensil the lab provided; and thus, they would expect to see pink ink. However, after a couple more futile attempts to print on the paper legibly with that pen, the Survey Participant became aggravated and threw the lab’s pen on the table. It bounced off onto the floor, where he left it. He said, “Ah, to ****with it! You win. We’ll do it your way. I’ll use your pen.” In a matter of seconds, the gentleman completed all the lab paperwork. He then sarcastically remarked, “Who’d figured you would need a decent pen to write with in a hospital?”

We then retired together to the open-cubicle stations in the recesses of the lab collection area where he could more discreetly, conveniently, and quickly complete the HR-QoL survey—and then afterward have his labs drawn. As we walked together, the Survey Participant fiddled with the pen passing it back and forth between his right and left hand. He marveled at it as if he were being transported to some wonderful place in his past, and he said, “This is a great pen! It’s balanced, see. These pens are not cheap either. I absolutely love these pens. They are the best!” He then revealed that he was retired but continued to work as a metal sculptor. Before his retirement, he had been an engineer and had used these same pens in his engineering work, and he found the pens to be durable, reliable, dependable, and user-friendly.

The Author asked him what kind of engineer he had been, and he responded that he specialized in ecological remediation projects. He had managed the largest and most complicated ecological remediation projects in the State of Texas—a state commonly known to be prone to large and involved ecological disasters. The Author showed great interest and revealed having worked on research remediation projects 10, 11 that required salvaging and that many of the remediation concepts were like those used in eco-disasters. This led to a relatively long discourse on remediation, with the Author mostly listening intently. At the end of this conversation, the Survey Participant was in a much more relaxed mood than he would have been from the usual formal approach to initiate a HR-QoL survey. The interlude appeared to provide the Survey Participant with breathing space for self-composure, assurance, and a second wind that quickly carried him through the HR-QoL survey.

At the conclusion of the survey encounter, the Author warned the Survey Participant to retract the point of the pen so that it would not leak in his shirt pocket or elsewhere. He replied that he knew all about this risk due to his experience with these pens but none-the-less thanked the Author for his concern and caring. He maintained that the pens were great. The Author thanked him for his interest and commitment to the survey and reminded him that he (the Author) expected him back in 3 more months to participate in another survey. He readily agreed.

Note: The aforementioned example has been repeated many times (approx. 96 to date) with more or less equally successful results.

Discussion

There Is little consensus and substantial controversy regarding gift giving and gratuities necessary to conduct survey research.12, 13, 14, 15 Nevertheless, most practitioners would concur that gift giving’s central importance is in terms of establishing and developing genuine rapport in addition to cooperation, trust, participation, and (re-) engagement. Such gift giving always implies that something be given in return. Good rapport always allows the researcher surveying to grasp and hold research participants’ attention and proceed with the survey interview with efficiency and validity. As such, gifts must be useful, meaningful, and relevant in terms of the context of the study project, which in this case was a decent pen for the completion of a survey and other documentation—especially other future non-study hospital documentation. Furthermore, gift giving must also make the Survey Participants feel special—that is, important, competent, comfortable, worthy, and cared for, and most importantly, treated with sincere interest.

Gift-giving must be more than mere obvious, clumsy dissemination of meaningless junk with logos, which appears to be pandering and bribing. Hence, Survey Participants were sanitarily hand-delivered better individual pens that were more valuable than the standard writing instruments left-out in public bins for the masses; and moreover, the Survey Participants could keep their survey pens for future use. The unique individuated pen dispensing method also symbolized a caring act of ensuring disease transmission risk reduction and reminded them about the importance and value of the survey itself—and consequently the importance and value of their continued active involvement with it.

Yet, the price of the pen is not so exorbitant that it might unduly affect patients’ responses (cf. 15, and also see 16) Life (HR-QoL)—it was merely a nice gesture—a token of appreciation and esteem. Nevertheless, it also was a necessity for completing the survey and related documentation—it made sense, especially in a hospital setting as evidenced by the Survey Participant’s sarcastic/ironic comment. As an analogy, the value of a gift of a glass of water to a drowning person in the middle of an ocean is senseless, counterproductive, and even insulting, whereas, to a person dying of thirst in a desert, it is the commonsense priceless difference between life and death and worthy of gratitude. In determining practical gifts for research participants, the context must be considered. In a hospital, even in this electronic age, there is still a plethora of paper forms—and a working pen becomes truly mighty because it is a thoughtful gift that is sure to come in handy.

Ultimately, the gift of the pen was only a means to facilitating reciprocal cooperation, and active participation, and fostering genuine rapport. However, it opened the door to a more important gift: lending an ear to patients’ interests, concerns, problems, challenges, and even life stories. The Survey Participant in this case wanted to talk about how the pen reminded him of when he was a great engineer working on great projects using pens like this one. The gift of the pen provided him the opportunity to talk about heartfelt things that were important to him. The Survey Participant probably walked away feeling much better than he had before. Also, such listening is the opportunity to gauge the degree to which a trusting relationship has been forged in the interest of advancing a research study.

Summary

The paramount lesson learned for advancing a research agenda is clear. Gift giving (i.e., Potlatch or Potlatch rituals) in the furtherance of research studies, though seemingly insignificant, substantially affects a pseudo-familiarity, and evokes social norms to reciprocate with enhanced rapport, enlistment, cooperation, participation, engagement, and compliance—and even establishes preconditions for continuance of social relationships.cf. 23, 5, 6 Researchers should calculate and consider gifts carefully and tactically in terms of practicality and the purpose/intent of the survey project and what the study hopes to accomplish (e.g., really good pens naturally go with important pen-and-pencil HR-QoL surveys). Gifts should also be an indication of the symmetry in the relationship between researchers and Study Participants.cf. 26 Possibly the greatest gift of all as a result, especially in the case of terminal disease patients, is the idea of tomorrow and more time.see4 Hence, in closing encounters, the Author always reminded that they will be seen again in the future for another survey encounter.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

UT-MDACC Institutional Review Board #2.

Consent for Publication

Yes.

Availability of data and materials

Yes, available on-line or provided by author upon request.

Funding

This work was supported in part by UT-MDACC in-kind support.

Authors’ Contributions

Non-applicable, there is one sole Author.

Acknowledgements

The Author wishes to gratefully thanks MM Connect for proof of concept. The Author gratefully acknowledges in-kind support of the Department of Lymphoma and Myeloma, UT-MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX. in the preparation of this manuscript. Also, the author thanks Mr. Jasper Olsem and Dr. Hans C. Lee, M.D. Principal Investigator for encouragement in pursuing the subject matter. The author also expresses appreciation to Ms. Aileen “Acey” Cho freelance-copy editor for proofing and copyediting drafts. The opinions expressed are solely those of the Author. Reprints and correspondence should be addressed to the author at, [email protected], [email protected] ,or [email protected] UT-MDACC, Unit 429, 1515 Holcombe, Houston, Texas, 77030-400, U.S.A.. (713-745-2207; 832-372-3511)

References

- 1.Simmel G. (1908) Exkurs über Treue und Dankbarkeit Soziologie Untersuchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung. Leipzig Verlag von Duncker Humblolt 389-390 & 590-592.

- 2.Mauss M. (2002) The Gift The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies.Trans. W.D Halls. London Routledge Classics. 1-17.

- 3.Bigus O. (1972) The milkman and his customers: A cultivated relationship. , J of Contem Ethn 1(2), 131-166.

- 4.Parsons T, Fox R, Lidz V D. (1972) The “Gift of Life” and its reciprocation. , Social Research, Death in the American Experience 8, 367-415.

- 5.M Van Hulzen. (2020) Gratitude and that which we cannot return Critical reflections on gratitude Zeitschrift für Ethik und. , Moralphilosophie 4(746), 109-119.

- 6.Johnson R J. University of Houston Dept. of SociologyCommunity Health Outreach Workers and AIDS Intervention: An Ethnographic Analysis Exit Strategies Giving the Gift of Tomorrow, Thesis. 98-102.

- 7.Ailawadhi S, Jagannath S, Narang M, Rifkin R M. (2020) Connect MM Registry as a national reference for United States multiple myeloma patients Cancer Med. 9(1), 35-42.

- 9.Rashid Y, Rashid A. (2019) Case study method: A step-by-step guide for business researchers. , International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18.

- 10.R J Johnson. (2015) Remediation for Human Research Subjects Protections Non-Compliance Concepts and Approaches. , Clinical Research & Bioethics 6, 3-1.

- 11.Johnson R J.Scientific Ethical integrity and human research Subjects protections non-compliance remediation Commentary on practical considerations and Implications. , Journal of Human Health Research 1(3), 23-24.

- 12.Becker R, Möser S, Glauser D.Cash vs. vouchers vs. gifts in web surveys of a mature panel study--Main effects in a long-term incentives experiment across three panel waves.Soc Sci Res. 81, 221-234.

- 13.Barilan Y M. (2002) Medicine as grooming behavior: potlatch of care and distributive justice Health An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health Illness and Medicine. 6(2), 237-259.

- 14.Morse J M. (1991) The structure and function of gift givin in the Patient-Nurse relationship. , J West Nurs Res 13(5), 597-615.